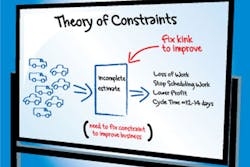

Tom Bemiller faced some big problems: a lack of skilled managers, an ineffective compensation plan and on-the-fly-scheduling. Frustrated with the shop dynamics, the general manager of 3D Collision Centers—which has five locations in the Philadelphia area—knew things needed to change. So, working alongside owner Dave Niestroy, Bemiller began to implement a management theory called Theory of Constraints (TOC), which aims to identify the limitations within a business that get in the way of efficiency and profitability.

Al Kollinger, president of Kollinger Auto Body in Wexford, Pa., and partner of the software consultancy Accelerate Inc., has been helping collision repair centers implement TOC for the past eight years. He and partners Steve Schaefer of Schaefer Auto Body Centers in St. Louis, Mo., and John Thompson of Global Focus in Lafayette, La., see impressive outcomes for the shops that successfully adopt the five TOC focusing steps and cause-effect logic. “Prior to implementing TOC, shops in our system usually have overall cycle times of 12 to 14 days. In our system, they have cycle times between four to eight days.” Net profit also has the potential to climb. “It can increase 10 to 25 percent, and I’ve seen it go as high as 100 percent,” Kollinger says.

IDENTIFYING CONSTRAINTS

Skip Reedy, president of CCPM Consulting in Seattle, Wash., and Phoenix, Ariz., has been working with businesses adopting TOC for over 10 years. He compares this management theory—created by Israeli physicist Eli Goldratt—to a garden hose. “Think of a garden hose as a system that moves water from one place to another,” he says. “If there’s a kink in the hose, the only way to get more water through that is to do something to the kink.”

So too for the kinks that disrupt the flow at your collision repair center. “A business is a system, and [likely] has at least one thing that is limiting its profits,” Reedy says. “Theory of Constraints identifies that constraint so we can focus our efforts there to improve the business.”

Rather than focusing on overall big picture changes, TOC helps you closely examine a few critical problem areas. “TOC identifies the few things that make a difference in the business,” Reedy explains. “It’s much easier to manage a business when you only need to pay close attention to those few things. Decisions become easier because the health of the constraint indicates how well the business is doing. If the constraint is limping, the business is limping. If it’s well, all is well.”

A typical collision repair constraint? The estimate. “Most of the time, people are scheduling based on unknown work content. The estimate is very seldom what it takes to repair the car, and sometimes that estimate can literally double,” Kollinger says. Meanwhile, cars keep coming in, and the work backs up. “That’s one of the biggest things I see—people keep bringing more cars in with no concern as to what’s in the shop,” Kollinger says. “Then what usually happens is someone says, ‘Stop. Don’t bring any more cars in for a week.’ They use that week to catch up, and then they start scheduling again, over and over again.” That reminds Kollinger of the adage that doing the same thing again and again but expecting different results is the definition of insanity.

SHOP SUCCESS

3D Collision Centers, which sees $10 million in annual revenue and has 60 employees, has been using the Theory of Constraints for a year. After trying to implement it on their own for a while, Bemiller and Niestroy enlisted Kollinger’s help. Bemiller says three areas of business have improved most dramatically because of TOC:

Management. “Prior to [implementing] TOC, our shops were very chaotic,” Bemiller says. “The success of one shop depended on us having a superstar manager who could just make things happen on his own.” The problem was that 3D only had one such manager who was able to pull the entire team’s weight. They struggled to find top managers to run the four other locations. TOC put some standards in place that reduced the reliance on a single individual. “After implementing TOC, the chaos in the shops is gone,” Bemiller says. “The shops now depend on a system. We can take a manager out of the system and the shop still runs.”

Compensation. Bemiller had been exploring different pay plans for three years before implementing TOC. But by applying “The Thinking Process” (a way to boil all your problems down to the root cause, Bemiller explains), 3D realized employees weren’t motivated enough to do a better job. “We realized we had to align the compensation at the local level,” Bemiller says. “We had to align the goals and rewards with the global goal of the company. A shop would do well and everyone would earn a bonus, and then we’d have shops that tanked, so the company as a whole didn’t make any money. Now, bonuses are only paid out when the [entire] company profits.” The collision center added a team-based commission structure to its hourly pay plan, which motivates employees to pull together and work efficiently. Both 3D management and its employees are happier with the results.

Scheduling. Bemiller admits 3D ran its scheduling by the seat of its pants, which caused huge problems with cycle time. TOC got the shop using a computer system that facilitates a better workflow. “The software we use helps us bring an ideal mix of work into our shops every day of the week,” Bemiller explains. “Before, we would bring all the work in on Monday/ Tuesday/Wednesday and attempt to get it all home Thursday/Friday.” Using the shop’s new scheduling software has created a much more stable flow through the system, Bemiller says. “We now focus on a complete estimate up front. We completely disassemble [the vehicle]. We’ve reduced our supplement ratio from 80 percent to less than 20 percent.” A new kitting process and inspecting parts for damage has helped keep that number low. “It eliminates a lot of last-second problems that cause chaos,” Bemiller says. Better yet, because of these changes and cycle time improvements, 3D has seen a 25 to 35 percent increase in revenue over the shop’s previous best months.

BETTER BUSINESS

Reedy says one of the perks of TOC is that it produces quick results because attention is focused on a specific problem area. “We improve the constraint and synchronize the rest of the business to it. Then we look for a new constraint and repeat the process. This is a process of on-going improvement that provides continually better results.”

Another perk: Employees are happier with a less chaotic work environment, Kollinger says. When he first introduces TOC to a shop, he asks the staff members to assess their current state of mind. “I’ll ask everyone on a scale of 1 to 10—1 you’re in heaven, 10 you’re in hell. Most everyone is closer to hell.” A few months later, he asks the staff to reassess. “Almost everyone who was at 7, 8, 9 is now 3, 4, 5. After going through [TOC], all that stress melts away.”

And that makes for better business, as Bemiller can attest: “Sales are up, profits are up and the company is much more stable and viable than ever before.”

Understanding TOC

Skip Reedy, president of CCPM Consulting in Seattle, Wash., and Phoenix, Ariz., explains the five steps of the Theory of Constraints (TOC):

Step 1: Identify the constraint. This is as simple as it sounds. Determine the problem area in your shop and then locate the source of that particular problem. For example, if cycle time is an issue, you may find that writing an incomplete estimate up-front is causing bottlenecks down the line.

Step 2: Exploit the constraint. Reedy says this means figuring out how to get more out of the constraint. For instance, if the constraint is a piece of equipment, and the person operating it leaves for lunch, you’re now losing throughput. So it may be wise to have an additional employee assigned to handle the equipment when the original operator is taking his or her lunch break.

Step 3: Subordinate to the constraint. You can’t ask the constraint to do things that aren’t necessary, Reedy explains. Let’s say the constraint is your estimator. If he or she is also responsible for fielding customer phone calls, that takes time away from doing their original job. It’s better to assign employees to single—or limited—tasks so throughput improves.

Step 4: Elevate the constraint. Reedy says this means getting more out of a particular constraint. This could mean hiring an extra person or buying an additional machine. Reedy points out that this is the first step in the TOC that involves spending money.

Step 5: Repeat steps 1-4. The Theory of Constraints is a continuous improvement process. Once one constraint is identified and resolved, begin at Step 1 again.

If you’re considering whether to implement TOC in your shop, here are a few helpful resources:

• The Goal by Dr. Eliyahu M. Goldratt. His book will help you determine if TOC is right for you and your business.

• Contact Al Kollinger at 412.889.3994 or at [email protected].

• Contact Skip Reedy at 425.923.5750 or visit ccpmconsulting.com.

—EL